Data corruption is not a big problem for many situations and use cases as long as it stays within limits.

The reason Netflix content cache appliances use one UFS file system per drive instead of ZFS (or any other RAID / volume management) is that they run at the edge of what the hardware can do and can tolerate failures up to and including data corruption (to a point).

It's a distributed cache and the video container formats have their own checksums.

If we look at windows server, macOS, Android. Those systems don't use file systems as resistant to data corruption as ZFS either.

And yet they are very popular operating systems..

What's also interesting. Despite the largescale nature of IT today, it is not really researched by large companies which file system leads to the most corrupt files in the long run, has the least fragmentation, best maintains its performance over a long time, remains the most stable over the years under heavy load.

If you go looking for reliable research regarding these topics you are going to find that there is very little large-scale, independent and highly funded literature to be found.

Instead, companies are more likely to engage in privacy abuses (Microsoft/Apple/Facebook/Avast/...).

Also, the most flawed programming languages are made the norm.

And then you have the many companies sitting around developing software for things for which perfectly working open-source alternatives have existed for decades. (Adobe, Jetbrains, Snowflake, Veeam, ..)

I have not done any scientific research, but this is my impression after having used FreeBSD (ZFS) and OpenBSD (UFS) as daily drivers for years.

For desktop use, it makes little difference which of the two file systems you use.

I have never seen corrupt files with either file system. UFS did not give any problems after power failures, it automatically fixed the filesystem after a reboot.

In terms of performance, I think it depends on the specific workload which one is going to be the fastest.

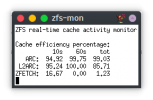

That you need 8GB of RAM for ZFS is also a myth. On the desktop, you can use ZFS just fine if you use 4GB of RAM.

I have done this for years without ever experiencing a problem.

There are certain useful features of ZFS such as compression and snapshots. For desktop use, ZFS snapshots also makes little difference.

If I use rsync to do monthly backups to a 20-year-old HDD, it almost never takes more than 90 seconds, so it's fast and convenient as well (for desktop usage).